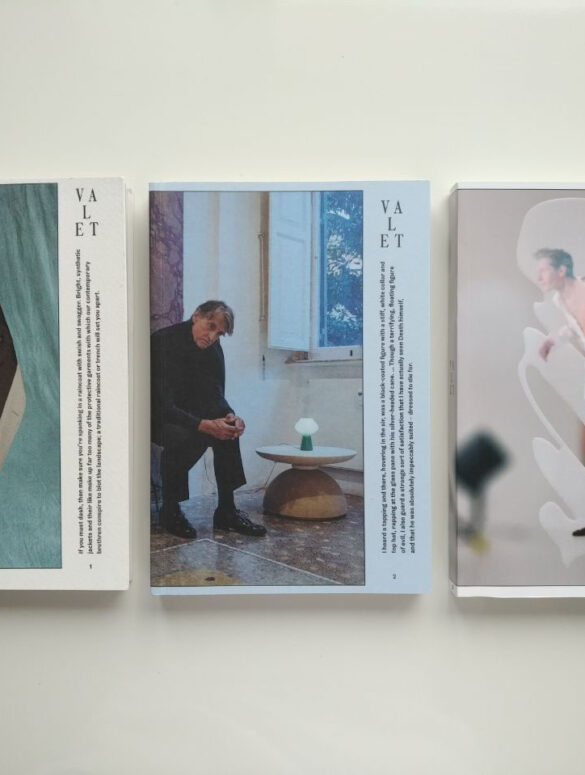

It may seem strange to praise print in an online magazine but I believe that digital is not the only way to live. So the contradiction is smaller than it appears to be at first sight because what we write about and show here is all about tangible things from the real world. Fabrics and leather. Tool and craftsmanship. Hands, feet and eyes. So when we first heard about VALET magazine we were keen to meet the founder. Here’s our exclusive interview with Luke Adams.

Feine Herr: What is the concept of Valet in a nutshell?

Luke Adams: Valet is somewhat a response to sartorial shallowness. We believe that the culture and history surrounding menswear — i.e. why we dress the way that we dress — is incomparably more interesting than what is often explored in media, such as the latest seasonal trends, the top-five must-have loafers for summer, or precisely how wide a lapel should be.

And we loathe the dearth of words in menswear cultural coverage, and so champion long-form essays that take unexpected and esoteric approaches to menswear and style, aiming to inspire men to dress entirely and unapologetically as themselves. Valet is a sort of celebration of our inspiration to care about what we wear, and to have engaging conversations on eternal subjects.

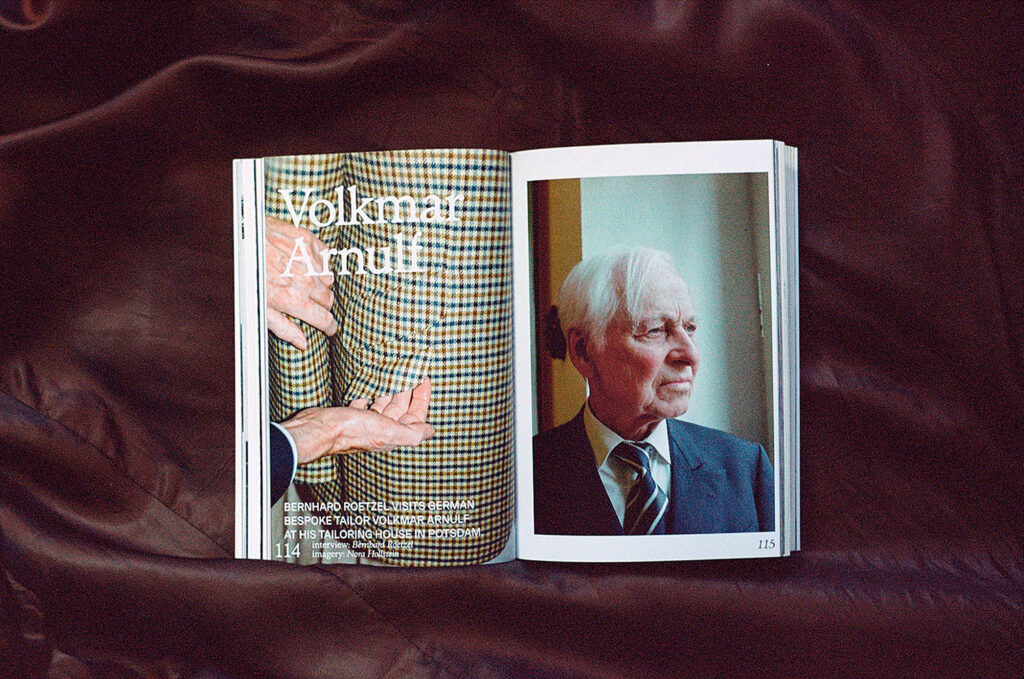

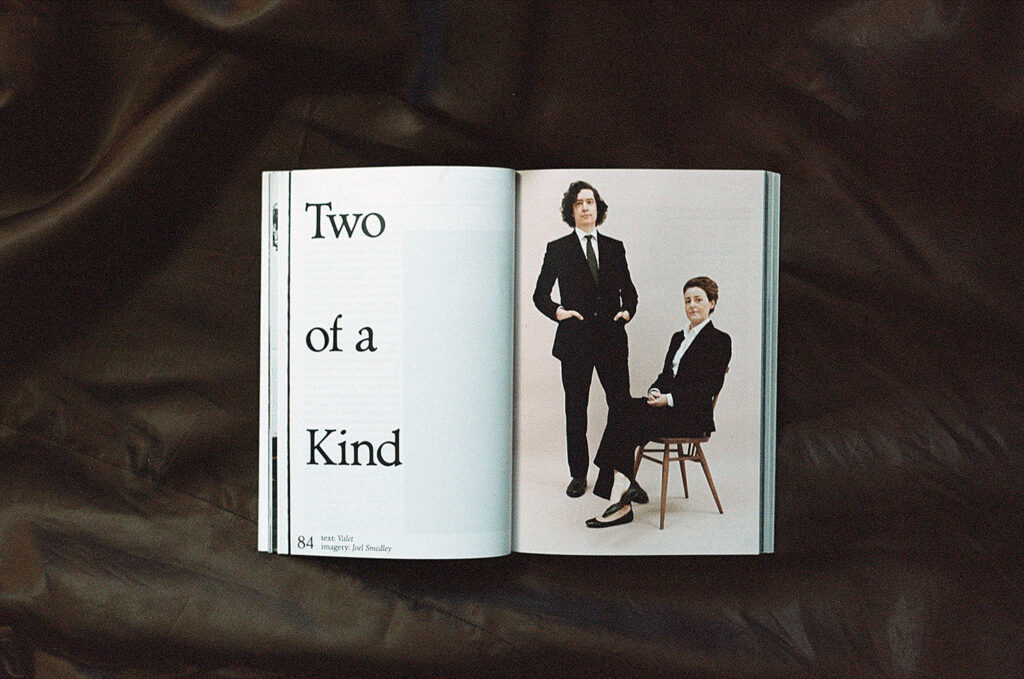

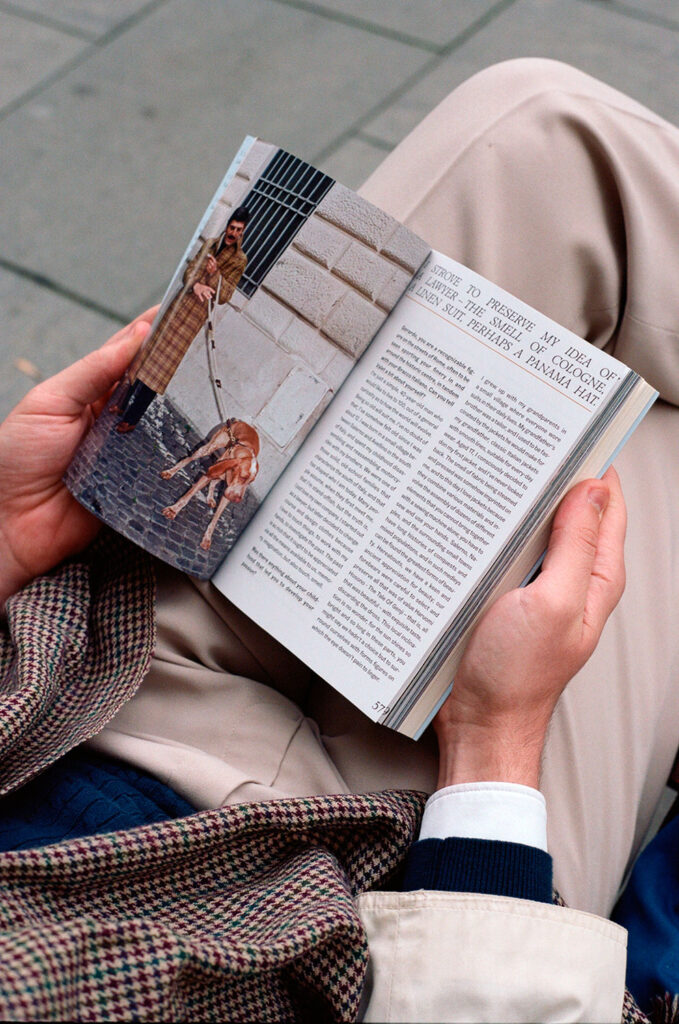

In terms of form, we publish long-form articles, essays, and photo-stories covering topics related to the culture of classic menswear. One criterion we have for what we publish is that it should be something different to what one might be able to find online. So no top-ten lists, no reviews, no catalogue look-books. Only in-depth essays that have shape and purpose, and remain relevant whether you read them today or in twenty years’ time.

How did you come up with the idea?

Valet started in a bar in St Petersburg some time in 2019. Its founders, Luke Adams and Kirill Savateev, worked for another prominent print magazine that took a specific subject — in this case speciality coffee — and used it to explore the Big Themes of life. We wanted to do the same with menswear and classic style. We knew we had something to say, and we knew that we lacked a publication that recognised the richness of the sartorial theme as an avenue by which to approach the world.

What is the idea of using pictures shot on film only?

While there is much to be said for the way film captures light and texture — essential subjects in menswear photography, it also captures mood. Moreover, in its very spontaneity, photographs shot on film simply feel more ‘alive’, and situations and atmosphere seem to find a clearer expression through that medium. I know this sounds wishy-washy, but could you really expect a more rational answer from a photographer?

How would you describe your readers?

Well, our readers, I should think, are much like us. Friends, chums, pals — people with whom we’d like to drink. For them, style is a true expression of character, a product of experience — not something that changes with the seasons, or that can be washed away by the tides of fashion. Our readers know that true style can never be torn down and started over; it must be built upon and truly refined.

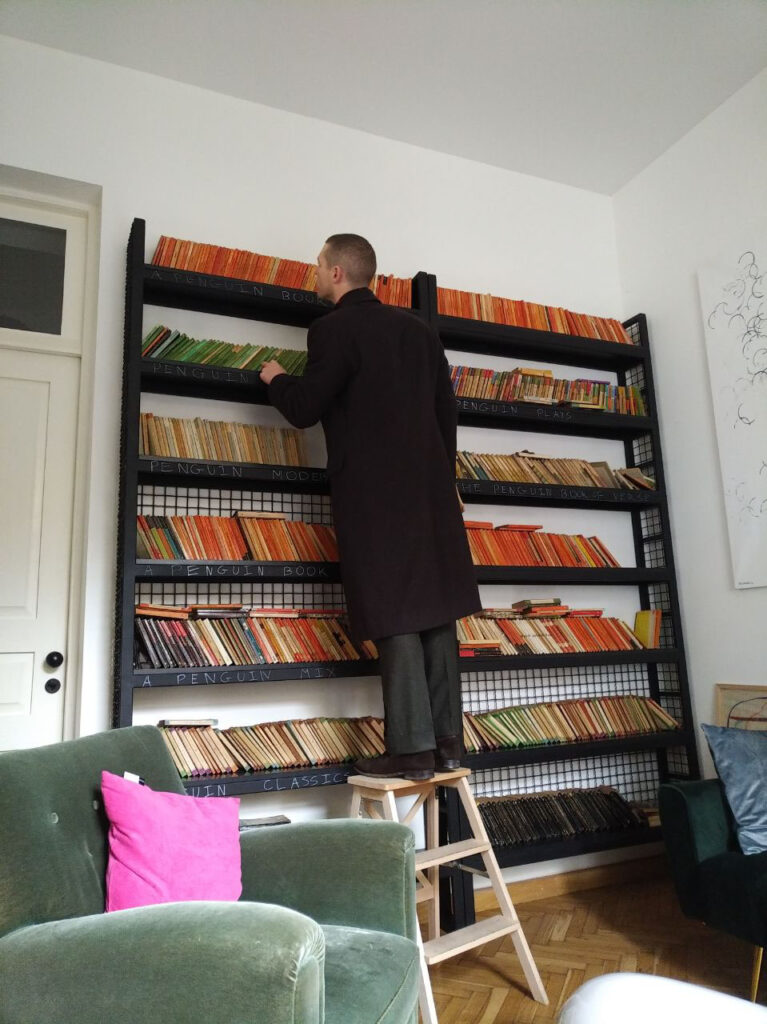

As to reading tastes, they have an appreciation for classic literature just as they do for classic clothing, and in their reading on the subject, they require depth and precedent—historical, philosophical, ethical, literary. They are people of detail, of patience, and therefore of good taste.

What is your concept of today’s gentleman?

I believe that many of the qualities I associate with gentlemanliness are truly timeless. What’s more, I believe that they are essentially simple: A gentleman is an artist, purely. Like any genuine artist, he occupies a world where curiosity, kindness, tenderness, ecstasy are the norm. These qualities alone can’t help but lead to the development of a character befitting a gentleman.

What is your personal idea of style?

At its best, style is inspiration — inspiring to the wearer but also to his fellow creatures. It involves a reconciliation of the fact of being an individual in a world populated by other individuals, and is therefore not only a form of self-expression, but a courtesy to others, a celebration of life. One should strive to cultivate both a sartorial and individual style befitting his character; one is nothing without the other. There is nothing enduring or eternal about an elegantly dressed bore or ass.

To me, there are three points of view from which an individual of refined style can be considered: as a dandy, as a paragon, and as an enchanter (to borrow a Nabokovism). The most stylish individuals combine these three —but it is the third that predominates and proclaims him a true artist of style.

To the dandy we turn for his supreme interest in novel colours and textures, his indulgence in accessory, and for the pleasure of imagining we had the confidence to dress quite like him. But in this last point we glimpse the limit of the dandy as inspiration: as with much of what is called modern art, the joy and comfort one experiences in its contemplation is partly the thrill of recognition that oneself could produce such a work, given the right circumstances. But true art is never simple; one should stand in awe at its alter, almost uncomprehending of how it was achieved.

A slightly different eye inclines towards the paragon — the apotheosis of elegant, classic style. Always the crisp white shirt; always the tasteful tie; always the pocket square sitting just so. He is the image of the classic gentleman, striding resplendent down St James’s in his bowler hat and tightly rolled brolly — in many ways a man after our own heart! Though an exemplar of the highest reaches of style that we as a civilisation have yet conceived, he flirts a little too closely with anachronism, and he can seem a little too buttoned-up, sometimes putting him at odds with the context in which he finds himself.

Finally and foremost, a man of style is an enchanter. What do I mean by this? Not only does he dress elegantly and classically; not only does he take joy in pleasing combinations and the individual flourish; not only is he in his manner in all ways gentlemanly; he combines these things with true charm, wit, and originality — he radiates a force of character, a refined personality, rent from his unique life experience. It is he who, on meeting him at a party, sticks in the memory; it is he who great writers immortalise in their memoirs; it is he and others like him that truly inspire others to strive to be better. We cannot help but to look upon him in wonderment and contemplate — both in terms of style and charm — the individual magic of his genius.

What are your favourite outfits?

I am a simple man; if I could wear grey flannel suits year-round, I would. I also fall into the camp of the slightly fogey-ish, adoring such things as threadbare tweed jackets, stiff cords, and off-white shirts. Having only once worked in an office (and loathed it), I can afford to wear slightly less ‘town’ colours and textures, and so I wear a lot of brown—in my view, an underexploited colour in menswear.

I have found, with time, that many of what may be termed my personal style flourishes resulted from mistakes or oversights. Something of a trite example, but: I like leaving the buttons on a button-down-collared shirt undone when wearing a tie, from time to time. I had simply left my flat without buttoning them once, and yet, on reflection, found that there was something about the shape of the collar when left unbuttoned that I find attractive, not to mention the fact that it does breathe a little insouciance into an outfit. I have always been slightly sceptical of a chap who’s turned out too well.