It’s just after eight in the morning. It’s quite cold at the end of November and it looks like snow. But it is still dry. I arrived in Bergamo the evening before. I still have 30 minutes before the driver arrives to take me to Thomas Mason’s company headquarters in Albino, a small town near Bergamo. I use it for a short walk into the old town. I buy a few postcards, stamps and a jar of Proraso shaving soap with the typical “Menta” fragrance. There are already a few people on the road, including some joggers.

At the congress of the World Federation of Master Tailors in Biella in August 2023, I met a Thomas Mason employee who I already knew from Vienna. At the time, she had visited my shirtmaker Nicolas Venturini. In Biella, she presented Thomas Mason’s fabric collections to the congress participants. Founded in 1796 by Sir Thomas Mason in Lancashire, the shirt weaving mill has been part of the Albini Group since 1992. During our conversation, we came back to the idea we had already had in Vienna that I should go and see how Thomas Mason’s fabrics were created in Italy. After the congress we talked about dates and finally my visit could be organized. So I flew from Hamburg to Milan and was driven from there to Bergamo.

The Albini Group is the world’s largest manufacturer of quality fabrics for shirts. Founded in 1876 in Albino near Bergamo by the Albini family, today under the management of the 5th generation. 1250 people work for the group worldwide and 20000 new fabrics are produced every year. 70 percent of production goes abroad, and 80 countries are supplied. It was a stroke of luck for Thomas Mason to join the Albini Group. The Italians have turned the traditional British weaving mill into a globally renowned brand. Without touching the core of the brand. Thomas Mason continues to stand for the highest quality, but above all for a certain style: the always bright colors and sometimes slightly daring designs associated with Jermyn Street shirts. Even if only a few truly English shirtmakers are still based there. This is because many addresses sell shirts that are neither made from English fabrics nor sewn in Great Britain.

Thomas Mason is one of the great English brands, and its importance for classic menswear would place it alongside names such as Aquascutum, Lock, Church’s and Swaine Adeney Brigg. The fact that it is not quite so well known is simply because Thomas Mason as a weaving mill has always taken a back seat to the shirtmakers and fashion houses it has supplied. This does not necessarily have anything to do with British understatement, but rather with a basic attitude that was typical of all European weavers. The name was probably familiar to the customers of British shirtmakers, of whom there were dozens in London during the golden age of bespoke culture, from the late 19th century until the beginning of the First World War and then again from the 1920s until the end of the following decade. Thomas Mason has been supplying the best addresses in London’s West End since 1796. And in 1936 the weaving mill became the exclusive supplier to Turnbull & Asser, the most elegant, innovative and perhaps most respected shirtmaker and outfitter in St. James’s.

The connection to the royal family came much later, in the early 1980s, through Prince Charles, the current king. He is an avowed customer of the company, T & A are Royal Warrant holders. By the end of the 1930s, however, Turnbull & Asser were already supplying an extremely select clientele, including Prime Minister Winston Churchill. He not only had shirts tailored at Turnbull & Asser, his legendary velvet overalls, the “Siren suits”, were also sewn for him there. Otherwise, the high nobility was rather less represented, which could be related to its thriftiness. Or with the somewhat glitzy image of the shirtmaker and outfitter. Turnbull & Asser distinguished itself from its competitors through its colors and patterns, which were always a little more modern and daring. The British refer to this style as “flamboyant”, and Thomas Mason can be considered the creator of this look, as the fabrics came from him.

The fact that Thomas Mason has not been weaving in Lancashire for over 20 years does not yet seem to have fully penetrated the consciousness of many Britons. In any case, Thomas Mason is often mentioned in the same breath as the manufacture of shirts in Great Britain when it comes to criteria as to whether a Jermyn Street shirtmaker offers a fully British product. Bergamo takes a relaxed view of this. Because in the end, this only proves that the Italian owners are continuing Thomas Mason’s style very skillfully. However, Albini did not physically take over any weaving machines, buildings, land, fabrics, employees or stocks, just the brand name and the existing customers. The only thing tangible was the archive of around 700 fabric sample books, which were shipped to Albino in special boxes and archived there in an air-conditioned room. Whereby the term archive is somewhat misleading. This is because the albums are ready for use, provided they are well enough preserved or have already been restored. In this respect, library would perhaps be a more appropriate term.

As the only tangible remnants of Thomas Mason’s history, these cloth books are a real treasure. They contain samples of English weaving art from the end of the 18th century to the end of the 20th century.

However, the long-term success of Thomas Mason is not only due to the skillful further development of the characteristic design, it is above all due to the quality of the fabrics. And this is the result of the “vertically integrated production process” within the Group. In other words, the production of Thomas Mason fabrics is in one hand, from the fiber to the finishing, i.e. the final refinement of the fabric. So no yarn is bought in, everything is home-made. And I saw that myself in Albino. As soon as I enter the production area, the typical smell of a cotton weaving mill fills my nose. It is difficult to describe – fresh, watery, woody. The pounding of the looms can be heard from afar. But first we walk past huge fiber bales. The bales look like gigantic sacks of absorbent cotton. The fiber material swells out white. I have the best raw material in front of me, it has traveled halfway around the world.

An employee explains to me what I have in front of me as we go from bale to bale. First of all, Egyptian cotton with a fiber length of up to 36 mm. Long fibers are easier to spin and make the yarn more stable and less prone to creasing. Egyptian cotton comes from a small region in the east of the Nile Delta, where it is picked by hand. A little further on is Giza 45, also known as the “Queen of Cotton”. Only 90 bales are produced each year. It has a particularly long fiber length of over 36 mm and an exceptional degree of uniformity. It is extremely fine, the fibers are only 2.95 micrometers thin. Giza 87 is a variety that is particularly suitable for designs with bright colors. The fiber length is 36 mm.

We walk a little further and stop in front of another bale. It contains Supima cotton from the US . Another classic among the varieties. 93 percent is grown in California in the San Joaquin Valley, with the remaining 7 percent spread across Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. This cotton is long-fibered but twice as thick in diameter as other varieties, making it particularly hard-wearing and durable. It is ideal for white fabrics.

With the next bale, the Italian’s voice takes on a reverent tone: Sea Island Cotton. Anyone who knows even a little about shirts knows what we’re talking about: The best of the best. A dream provenance for the finest fabrics. When shirtmakers show samples of it, it gets expensive. The Italian pulls out a few fibers and gently strokes them. Sea Island cotton is the oldest and rarest variety, grown in Antigua, Jamaica and Barbados. The yield is very low, amounting to only 90 to 160 bales per year worldwide, which corresponds to 0.006 percent of global cotton production. The fiber length is 37 mm and above.

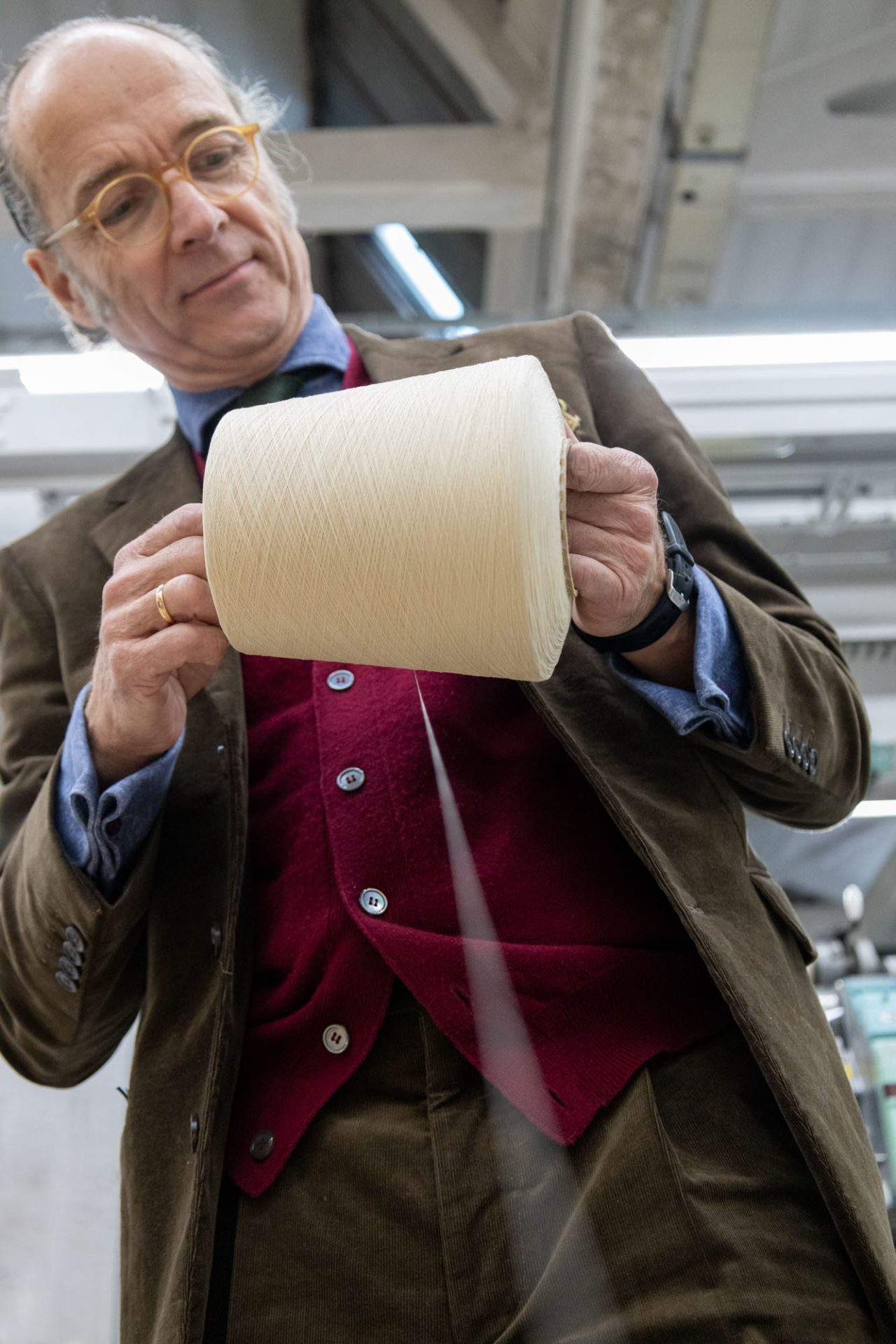

This fiber material must first be transformed into yarn. The fiber material is gradually thinned and lengthened until it is finally twisted into a thread. What an employee demonstrates to me with his fingertips on a tuft of fiber is done by machine in several stages. The end result is large spools of yarn, which are then dyed. After dyeing, the yarn has to undergo a few more treatments: it is washed, excess color is removed and finally dried using a combination of centrifugal force and radio waves. Of course, it must be ensured that the colors are reproduced exactly again and again, often over decades. This requires a great deal of effort for a natural material such as cotton fiber. An entire team is working in a dedicated laboratory to ensure this. It looked a bit like the “mad professor’s” study. I was particularly impressed by the drawers with the yarn samples in various colors.

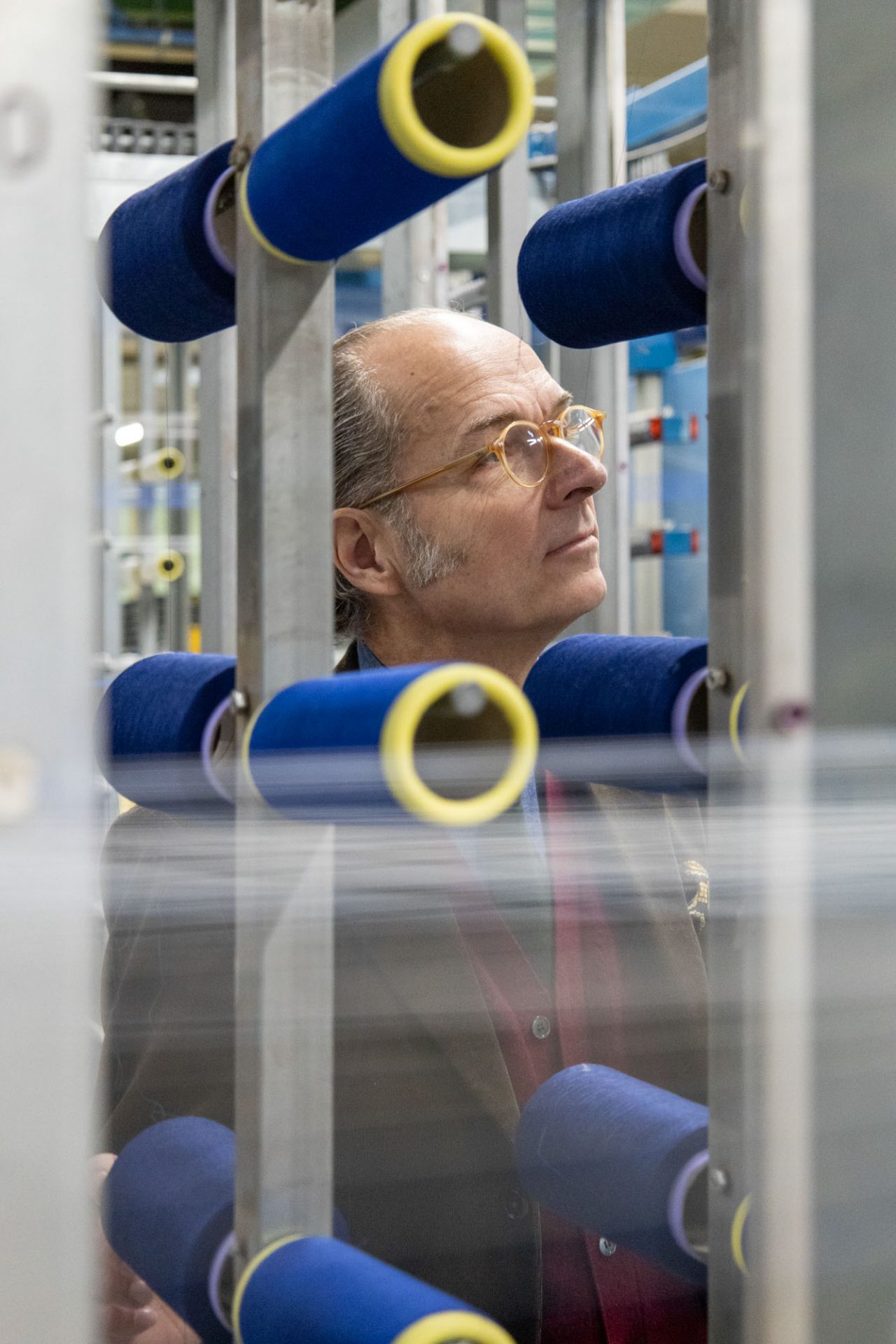

The individual yarns are now twisted together. A twisted yarn, i.e. a multiple yarn, is more stable and less prone to creasing. Depending on whether two, four or eight threads are spun, the yarn is called two-strand, four-strand or eight-strand. High-quality shirting fabrics are always made from twisted yarns, which is referred to as “full ply”. Which brings us to the next step in the creation process: weaving. A fabric is created by crossing longitudinal and transverse threads. The tautly stretched longitudinal threads are called warp, the transverse threads weft. The cross thread is “shot through” over or under the warp at a set rhythm. As the word suggests, weaving is a very noisy business. The preparatory work, on the other hand, is largely done in silence. The looms are ammunitioned, so to speak, i.e. loaded with yarn. The best way to imagine the effort involved is to look at a shirt fabric with a magnifying glass. If the magnification is sufficient, the individual threads of the tissue are recognizable. All of them are threaded lengthwise into the loom beforehand to form the warp. In the past, this was manual work, today it is only partly manual work. Nevertheless, it remains a time-consuming process.

Now it’s getting loud. The pounding of the looms, which I had already heard muffled as I entered the factory hall, is now ominously close. Before we enter the weaving room, earplugs are distributed. And then you can watch how the materials are created. What was previously hundreds of individual threads is combined into one fabric in the loom. It jerks forward across the width of the loom. I involuntarily clasp my hands behind my back, because somehow these machines, whose volume is only partially defused by the earplugs, look menacing. But noise and vibration create a wonderful structure, a fabric that is later transformed into a garment by shirt tailors. Whenever I am allowed to watch a modern weaving mill, I feel great respect for the cultural achievement required to produce something as commonplace as fabric.

Weaving itself is an ancient technique that has been documented in Mesopotamia since the 7th millennium BC. Weaving has been used in Europe since around 4000 BC. And with Thomas Mason since 1796. But we are in the year 2023 and here in Italy I see state-of-the-art technology. As we leave the weaving room and take out our hearing protection, you can see on everyone’s face how fascinating weaving is, even for those who work with it every day. However, I am almost more impressed by what has to happen to the fabric after weaving until it is transformed into what we are presented with at the shirtmaker. When the fabric comes out of the loom, it is hard and scratchy to the touch. Only the finishing process gives it the desired softness, sheen and silky feel.

As everything is done under one roof at Albini, I was able to see how the Thomas Mason fabrics are finished. There are weavers who do not finish their fabrics themselves and pass them on to external service providers, not so at Thomas Mason. Finishing fabrics generally means that they are treated with water, detergent and heat as well as mechanically. Water causes the fibers that make up the yarn to swell, and they contract again when heat is applied. The trick is to wash the fabric at a certain temperature for just long enough to give it the right softness after drying. The desired surface structure and “feel” are also produced during the finishing process. The aim of a poplin is to achieve the smoothest, almost shimmering surface possible. The smallest fiber ends that protrude from the fabric are flamed, then the fabric is ironed smooth and pressed. With a flannel, on the other hand, the fabric is mechanically roughened and then brought back into shape with steam. All in all, refinement is a process that is as crucial as it is complicated. In the past, it had a lot to do with feeling and experience; today, technology is used. Which, however, is permanently controlled by humans.

In the last step of production, the final inspection, the technology only provides auxiliary services, everything else is done by the employees. I have never actually seen men doing this work in a weaving mill. In Huddersfield, in England, it was explained to me that men simply don’t have the patience. Perhaps not the exact eye either. The women in front of whom the lengths of fabric were slowly being unwound had to smile at my story. They never took their eyes off the fabric, marking tiny mistakes again and again. When I tried it myself once, I could only find a fraction of the places to be criticized. And after five minutes I was no longer able to look.

The final inspection is a key distinguishing feature between top weaving mills and the large midfield. For shirtmakers and shirt manufacturers, however, it is extremely important that the fabrics arrive in perfect condition. Flawless and fast. This is particularly true in the bespoke sector. And who doesn’t Thomas Mason supply? No matter which chemist you visit in the world, Thomas Mason fabrics are likely to be found there. Whether in the form of pattern books, in one piece or even in exclusively woven qualities. However, if a shirtmaker doesn’t have any fabric in stock or the customer chooses something from the fabric sample books, then the desired item should end up on the cutting table as quickly as possible. Thomas Mason guarantees delivery within 24 or 48 hours, depending on receipt of the order and distance.

A dedicated team of employees takes care of shipping. Although they are supported digitally, their eyes and hands are also crucial here. This is because the final quality control takes place on the ladies’ cutting tables, where the fabric is cut by hand according to the order and prepared for dispatch. This is achieved with a mixture of speed and precision, spiced up in the Italian manner with a pinch of charm and humor. Rolls of fabric and scissors are handled with great routine, the employees joke with each other, but are also remarkably polite. I watch for a moment. The rolls of fabric are brought to the cutting table in a trolley. The employee checks the barcode, it beeps, then she pulls out the first roll. She removes the plastic cover, unrolls the fabric onto the table and measures the desired length. She scrutinizes it and actually discovers a stain. She cuts off the affected piece, unrolls a new length, measures and finally cuts. It all happens in a flash. Then she pulls out the other four rolls and proceeds again in the same order. As this delivery is destined for Europe, it will end up back on a cutting table 24 hours later. With a shirtmaker who will sew something made to measure for a customer.

The tour on the first day ended with a visit to the archive. It is located next to the design department, which is of course no coincidence. This is because the fabric designers responsible for the Thomas Mason collections always get inspiration for their work there. They say that there is nothing new in fashion. That’s true to a certain extent. When you leaf through the albums, in which thousands of fabric samples from almost 230 years of company history are glued in, framed on many pages by handwritten notes in pencil or ink, then you gain respect for the designers of today, who add something to this huge mountain of already accomplished design art. However, what is being created today is not really new. And if so, then rather through reduction. Many fabrics could no longer be produced in this way today, as the loom would have to be operated entirely by hand. Which is no longer possible today. Even if some of the albums look as if they contain manuscripts from a monastery library, their contents are of the highest standard in terms of web technology.

I could have spent a whole day in the archive. On the one hand, because of the immense wealth of materials. On the other hand, however, because the dates in conjunction with the notes stimulate the imagination. What life stories are hidden behind the notes, the quick additions? And what has become of the fabrics selected by customers from these books? And above all from the people who wove, processed, sold, bought, wore, inherited, in short, lived with and in these fabrics? The archive is also available to customers who wish to have their own fabrics woven for their collections. Visitors from all over the world come to Albino just to be inspired by what Thomas Mason suggested for the summer of 1865, the winter of 1907 or the spring of 1966.

I was then presented with what is happening at Thomas Mason today in the evening. The old fabric books were put back on the shelves and the latest collections were put on the table instead. The three best known are Silverline, Goldline and Bespoke. The Silverline books contain all the classics, some of which have been known for decades, supplemented by seasonal novelties for spring and summer as well as fall and winter. The Goldline fabric books, discreetly bound in brown linen, contain the lace qualities and, as the icing on the cake, the fabrics from David & John Anderson, another traditional English brand that belongs to the company group. The books in the Bespoke collection contain fabrics that are all available in “cut length”, i.e. in the minimum quantity for a shirt, so this is the collection for the artisan chemist. The fabrics in the Bespoke collection are all shipped worldwide within 24 or a maximum of 48 hours. In addition to these three collections, there is also a separate collection with fabrics made from Sea Island cotton, the books with fabrics from Giza 87, the crease-resistant and easy-to-iron qualities called Journey and the super luxurious “shirtings” from the Diamond collection. Having the collections presented in the Thomas-Mason archive was particularly appealing, as it provided a link to the past. And proved that Thomas Mason can also come up with very exciting collections in 2023.

During my visit to the Thomas Mason archive, I met Stefano Albini, President of the Albini Group, for an interview. Read the interview here as a continuation of the report on my visit to Thomas Mason in Albino.